For decades, the Nairobi River—once a vital artery of the capital—has been reduced to a channel of raw sewage, industrial effluent, and garbage, endangering health and livelihoods. Now, the government has unveiled an ambitious KSh 50 billion Nairobi River Regeneration Program, described as one of the most transformative urban renewal projects in Kenya’s history.

President William Ruto launched the project in March 2025, designating the 27.2-kilometre river corridor as a Special Planning Area (SPA). The initiative seeks to reverse decades of pollution and neglect, reduce flooding, and reclaim the river as a public asset by 2027. It combines ecological restoration with affordable housing, modern infrastructure, and accessible public spaces.

Under the plan, more than 80 per cent of pollution points are expected to be eliminated through a new 60-kilometre trunk sewer line, constructed wetlands, and an expanded Kariobangi Wastewater Treatment Plant with a daily capacity of 90,000 cubic feet. A 45-metre riparian buffer on both sides of the river will also be reclaimed and converted into parks, tree corridors, and engineered banks to curb flooding.

The regeneration program also addresses housing and livelihoods. It will deliver 10,000 affordable housing units and market spaces for 20,000 traders, replacing flood-prone shanties in Shauri Moyo, Mathare, and Dandora. Authorities have assured residents that no relocations will take place without due process and that public participation will guide every step.

A healthier, more connected city is also envisioned, with a 27.2-kilometre non-motorized corridor stretching from Ondiri to Ruai, complete with walkways, cycling lanes, riverfront parks, community centres, and libraries.

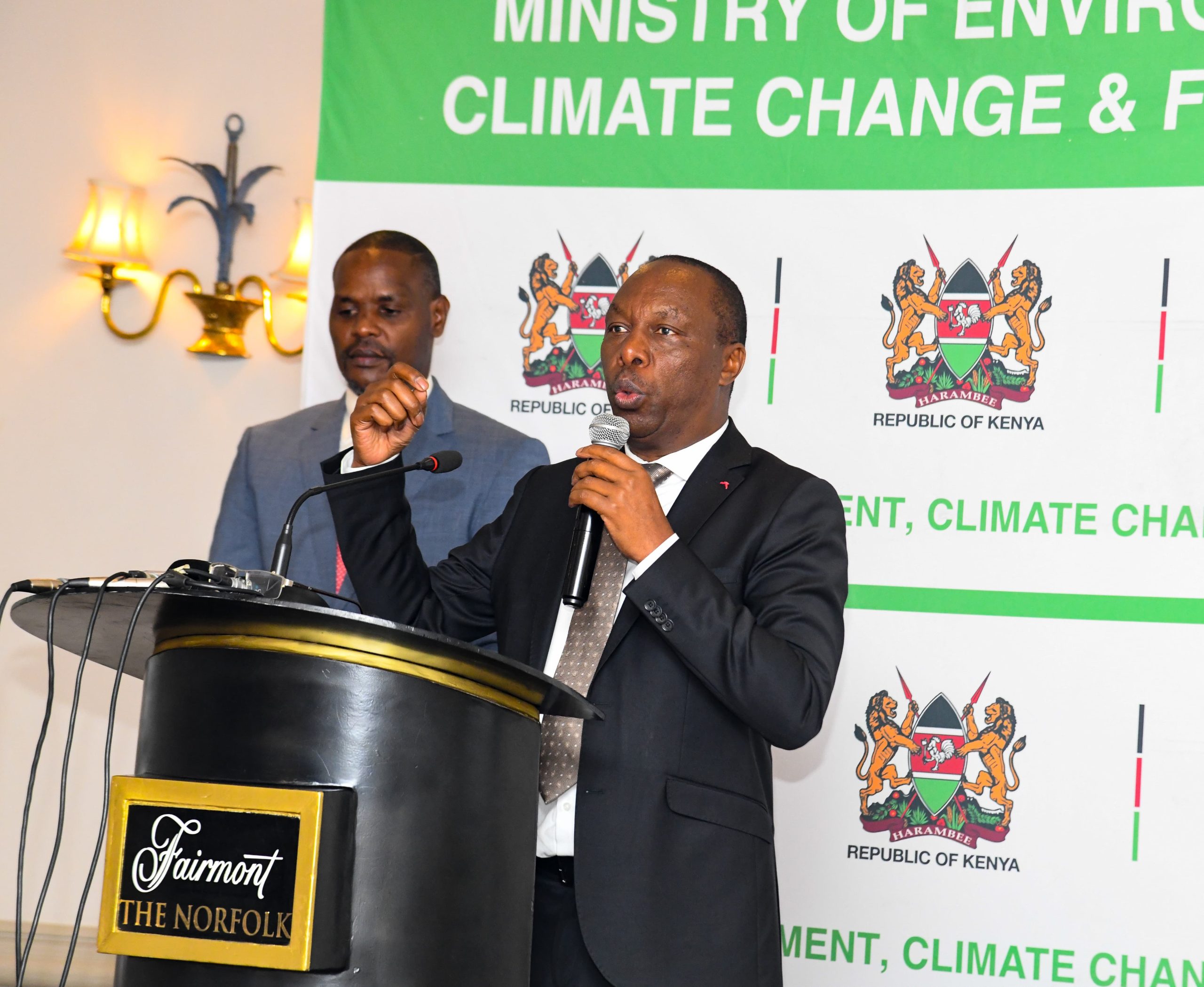

Officials emphasise that the program will only succeed with transparency and active public engagement. The SPA process, anchored in the Physical and Land Use Planning Act, will involve town halls, forums, radio campaigns, and other platforms before the final Integrated Development Plan is approved in 2027.

“The Nairobi River is not a dumping ground. It is a living ecosystem that must be protected for future generations,” said Arch. Mumo Musuva, Commissioner at the Nairobi Rivers Commission. His colleague, CEO Rtd. Brigadier Joseph Muracia, added: “Imagine walking, jogging, or cycling safely along a green corridor that links communities across Nairobi. That is the future we are building.”

The urgency of the initiative is underscored by a worsening sanitation crisis. Only about 20 per cent of urban Kenyans are connected to proper sewer systems, according to environmental activist David Wakogy of Friends of Ondiri Wetland Kenya. He notes that raw sewage often finds its way into rivers through leaking septic tanks, illegal discharges, and poorly maintained infrastructure, fuelling outbreaks of waterborne diseases.

“This is not just a sanitation issue. It’s a public health emergency and an environmental justice crisis,” Wakogy said.

By 2027, the government expects the program to deliver an 80–90 per cent reduction in pollution points, a 50 per cent drop in flood-related displacements and waterborne diseases, and a 30 per cent increase in land value along the river corridor.

“The Nairobi River is our shared responsibility. Together, we can turn it from a flowing gutter into a national treasure,” said Henry Ochieng, CEO of the Kenya Alliance of Resident Associations (KARA).