Dr. Waleed A. Madibo, Fulbright Scholar, Founder and President of Sudan Policy Forum.

“Tyranny is built on pillars of fear, falsehood, and silence.”

— Khalil Gibran

In the heart of Sudan’s ruin, the “Koznostra” still performs its sacred rites in the shadows — a cabal no different from Sicily’s infamous Cosa Nostra, save for one detail: it cloaks itself in religion and pretends to piety. Just as mafia loyalty is sworn behind closed doors, the Sudanese khoz pledges allegiance not to the state, but to the network; not to the homeland, but to the organization. This is a mafia with a religious mind — skilled in political blackmail, laundering money through “charitable” fronts, and dividing spoils in closed-door meetings reminiscent of mafia dons and Godfather councils.

This Koznostra does not believe in democracy, but in blind allegiance to its own devil. It respects no law — only the machinery of tamkin (empowerment). It does not fear God, only exposure. It monopolizes power, wealth, and the collective memory, unashamedly using tribe and region as shields for its violations. And when it withdraws, it leaves behind only rubble and disgrace — both dumped on the innocent people of the very regions it claimed to protect.

The term Cosa Nostra, Italian for “our thing,” speaks of secrecy and exclusivity — an ethos tragically mirrored in Sudan when Islamists formed a clandestine order that captured every limb of the state and governed it with the logic of a cross-border crime syndicate. Sudan’s own “Cosa Nostra” ruled in the name of northern peoples, while subjecting them to suffering — much like its Sicilian counterpart, which brutalized the very people it claimed to defend.

It is time we name the truth without fear or flattery: we must clearly and unequivocally disown every criminal who hides behind tribe, every corrupt man who uses regional identity to mask his crimes. There is no honor in a crime committed in our name, and no excuse for those who remain silent. If once the Sudanese “center” was defined by ethnic and regional privilege, that veil has now fallen. The fire now burns indiscriminately. No one is spared by tribe, and no one can hide in the shade of region.

Today, we are all gripped by collective regret, gnawing at our hands over a country lost to the greed of murderers and the silence of the wise.

There will be no salvation unless we rid ourselves of the mad captain steering us to the abyss — a man obsessed with power and wealth, who sees the nation not as a people, but as personal property, a battlefield for vengeance, a resource mine for his whims. To him, Sudan is no homeland, but a hostage.

The regime known as al-Inqaz (The Salvation) devoured our institutions, looted our legacy, and destroyed our economy — but it failed to fully erase our consciousness. From the far north to the deep south, from Port Sudan to Nyala, the people ultimately rejected its deception. Despite the mistrust and sectarianism it sowed, many hearts remained unyielding.

When Nafi Ali Nafi and Ali Osman toured the far north in the early days of the regime, trying to sell their Islamist project wrapped in ethnic supremacy, the locals fired back with sarcastic defiance: “Moses is from here. Jesus is from here. Muhammad is from here. God Himself is from here!” A biting, unforgettable joke. It wounded, but did not deter. So they repackaged their poison — mobilizing the north against the “margins,” hoping once again to consolidate control. But a generation of enlightened northern voices stood up and said it plainly: “Not in our name. Not this time.”

And if I once focused my critique on the historical centralization of power, today I must offer a just correction: northern Sudanese — though not subjected to genocide like Darfur, South Kordofan, and Blue Nile — were still humiliated, impoverished, and subjugated. It is unjust to blame these proud, dignified peoples for crimes committed by a cabal that hijacked their name and wore their identity as a mask — much like my own kin did at times. I do not absolve any who dipped their hands in Sudanese blood under the excuse of “natural selection” enforced by the Islamist security state.

The elite of the center suffered twice over: first, when the regime uprooted their political and economic foundations; then again, when the war erupted in the heart of Khartoum, unleashing chaos on all its inhabitants. What followed was a wholesale collapse — displacement, humiliation, starvation, and destruction that spared no one.

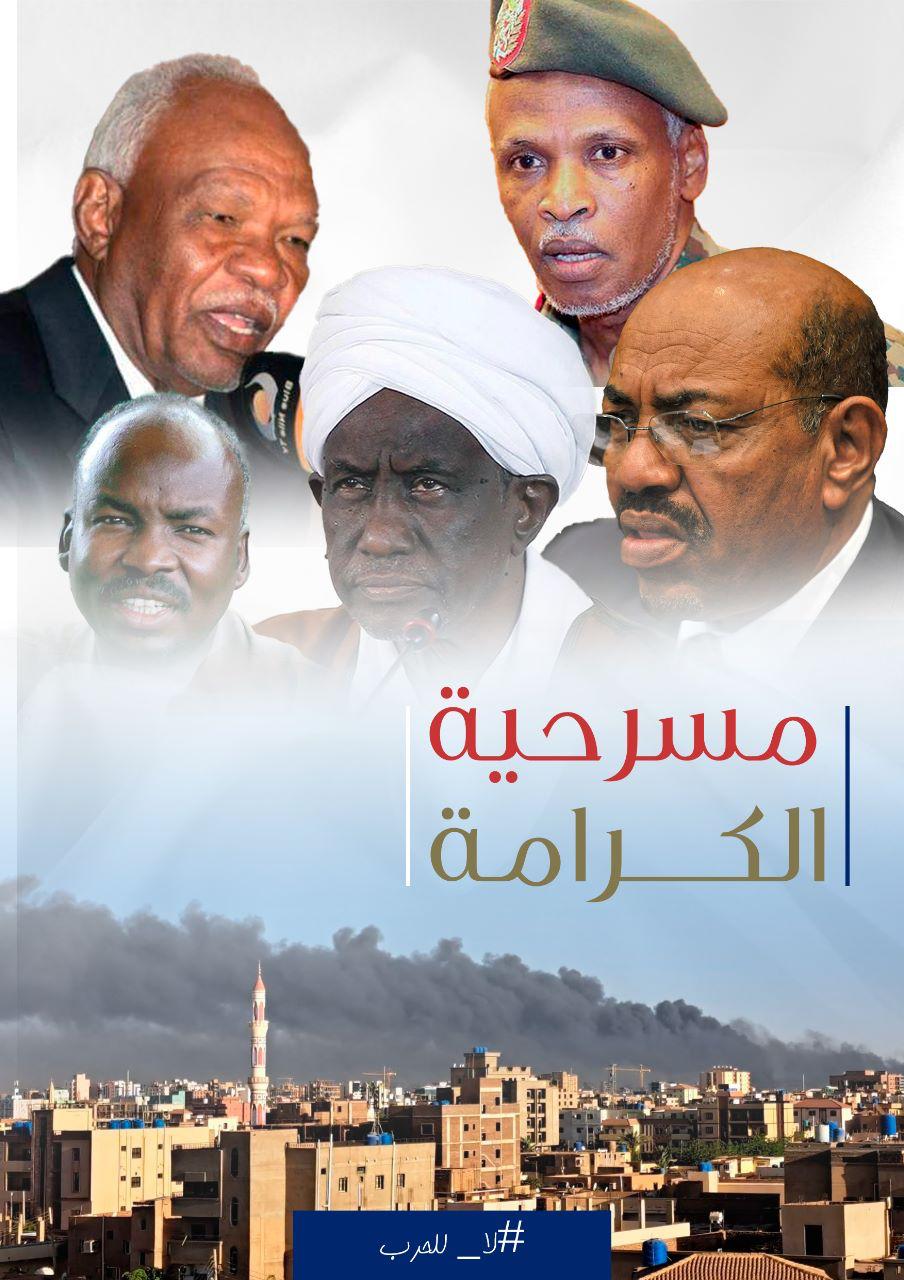

What remains of this Islamist gang no longer governs — it merely performs in a tragic play. In Port Sudan, there is no state, only a hollow spectacle: a general without leadership, a military without doctrine, and a farce called “Karama” (Dignity) that now provokes national shame. What’s left of the army is a sectarian militia waging war for Islamist-tribal alliances and gold-laced interests. The country is being looted and scorched while these elites spirit their families abroad and watch from balconies of safety and foreign comfort.

In the end, this moment in history demands a moral choice that cannot be postponed: We either continue justifying murder in the name of tribe, region, and religion — or we finally rise as a nation, rejecting falsehood and breaking the spell of tyrants who see our homeland as nothing more than spoils.

This is no longer a political dispute. It is a criminal syndicate draped in statehood, now ready to burn what remains to save itself. But we still have a chance — if we summon the courage — to sever the arteries of this Koznostra, and forge a new nation, ruled not by killers, but by truth.

Sudan is not dead. It is waiting — for someone to finally say: “Loyalty to the nation, not the mafia.”